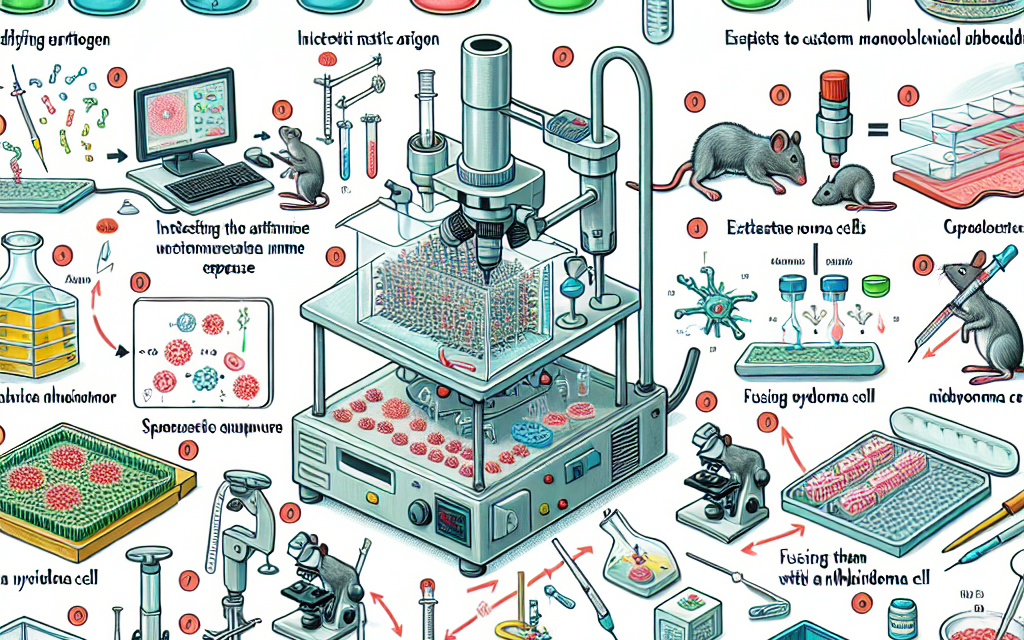

Crafting Custom Monoclonal Antibodies: A Comprehensive Step-by-Step Guide

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have revolutionized the fields of diagnostics, therapeutics, and research. Their specificity and ability to bind to unique epitopes make them invaluable tools in various applications, from cancer treatment to infectious disease detection. This article provides a comprehensive guide to crafting custom monoclonal antibodies, detailing the step-by-step process, methodologies, and considerations involved in their development.

1. Understanding Monoclonal Antibodies

Before diving into the crafting process, it is essential to understand what monoclonal antibodies are and how they differ from polyclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies are identical antibodies produced by a single clone of B cells, targeting a specific antigen. In contrast, polyclonal antibodies are derived from multiple B cell clones and can recognize multiple epitopes on the same antigen.

1.1 The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are produced through a process called hybridoma technology, which involves the fusion of myeloma cells with B cells that produce the desired antibody. This fusion creates hybrid cells, or hybridomas, that can proliferate indefinitely while producing a single type of antibody. The key steps in this process include:

- Immunization: An animal, typically a mouse, is immunized with the target antigen to elicit an immune response.

- Cell Fusion: The activated B cells are fused with myeloma cells to create hybridomas.

- Selection: Hybridomas are screened for the production of the desired antibody.

- Cloning: Selected hybridomas are cloned to produce a stable cell line.

- Antibody Production: The cloned hybridomas are cultured to produce large quantities of the monoclonal antibody.

1.2 Applications of Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies have a wide range of applications, including:

- Therapeutics: Used in the treatment of various diseases, including cancers, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases.

- Diagnostics: Employed in assays and tests for disease detection, such as ELISA and Western blotting.

- Research: Utilized in various research applications, including flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry.

Understanding these foundational concepts is crucial for anyone looking to develop custom monoclonal antibodies.

2. Designing the Antigen

The first step in crafting custom monoclonal antibodies is designing the antigen that will elicit the desired immune response. The choice of antigen is critical, as it directly influences the specificity and efficacy of the resulting antibodies.

2.1 Selecting the Right Antigen

When selecting an antigen, consider the following factors:

- Target Specificity: Choose an antigen that is unique to the target cells or pathogens to minimize cross-reactivity.

- Immunogenicity: The antigen should be capable of eliciting a strong immune response. Proteins and polysaccharides are generally more immunogenic than nucleic acids.

- Size and Complexity: Larger and more complex antigens tend to be more immunogenic. Aim for antigens that are at least 5-10 kDa in size.

2.2 Antigen Preparation

Once the antigen is selected, it must be prepared for immunization. This may involve:

- Purification: Isolate the antigen from its source to ensure purity and reduce contaminants that could affect the immune response.

- Conjugation: If necessary, conjugate the antigen to a carrier protein (e.g., keyhole limpet hemocyanin) to enhance immunogenicity.

- Formulation: Prepare the antigen in an appropriate buffer or adjuvant to optimize the immune response during immunization.

Proper antigen design and preparation are crucial for the success of the monoclonal antibody development process.

3. Immunization and Hybridoma Generation

The next step involves immunizing the chosen animal model and generating hybridomas. This process is critical for producing the desired monoclonal antibodies.

3.1 Immunization Protocol

The immunization protocol typically involves multiple injections of the antigen to boost the immune response. Key considerations include:

- Animal Model: Mice are the most commonly used model, but other species like rats or rabbits can also be used depending on the application.

- Adjuvants: Use adjuvants to enhance the immune response. Common adjuvants include Freund’s complete adjuvant for the initial immunization and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant for subsequent boosts.

- Injection Schedule: Administer multiple boosts (typically 2-4) at intervals of 2-3 weeks to maximize antibody production.

3.2 Cell Fusion and Hybridoma Selection

After sufficient antibody production is achieved, the next step is to harvest the spleen cells from the immunized animal and fuse them with myeloma cells. This process involves:

- Cell Harvesting: Isolate spleen cells using standard tissue dissociation techniques.

- Fusion: Use polyethylene glycol (PEG) or electrofusion to facilitate the fusion of B cells and myeloma cells.

- Selection: Culture the fused cells in a selective medium (e.g., HAT medium) that allows only hybridomas to survive.

Screening for hybridomas that produce the desired antibody is a critical step. This can be done using techniques such as ELISA or flow cytometry to identify positive clones.

4. Characterization and Optimization of Monoclonal Antibodies

Once hybridomas are generated, the next step is to characterize and optimize the monoclonal antibodies produced. This phase is essential for ensuring that the antibodies meet the required specifications for their intended application.

4.1 Screening for Specificity and Affinity

Characterization begins with screening for specificity and affinity. This involves:

- ELISA: Use enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to assess the binding affinity of the antibodies to the target antigen.

- Western Blotting: Confirm the specificity of the antibodies by detecting the target protein in complex mixtures.

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze the binding of antibodies to cells expressing the target antigen to evaluate specificity in a cellular context.

4.2 Isotype and Subtype Determination

Determining the isotype (IgG, IgM, etc.) and subtype of the monoclonal antibodies is crucial for understanding their functionality and potential applications. This can be achieved through:

- Immunoassays: Use specific antibodies to detect the isotype of the produced mAbs.

- Sequencing: Sequence the variable regions of the antibodies to confirm their identity and isotype.

4.3 Optimization of Production

Once promising candidates are identified, optimizing the production process is essential for scaling up. Considerations include:

- Cell Culture Conditions: Optimize media, temperature, and CO2 levels to enhance hybridoma growth and antibody production.

- Harvesting Techniques: Implement efficient harvesting methods to maximize yield while maintaining antibody integrity.

- Purification Methods: Use affinity chromatography or other purification techniques to isolate the antibodies from culture supernatants.

Characterization and optimization ensure that the monoclonal antibodies produced are of high quality and suitable for their intended applications.

5. Applications and Future Directions

The final step in crafting custom monoclonal antibodies is understanding their applications and exploring future directions in the field. Monoclonal antibodies have a wide range of uses, and ongoing research continues to expand their potential.

5.1 Therapeutic Applications

Monoclonal antibodies are widely used in therapeutics, particularly in oncology. Examples include:

- Rituximab: A chimeric monoclonal antibody used to treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

- Trastuzumab: A humanized monoclonal antibody targeting HER2, used in breast cancer treatment.

These therapies have significantly improved patient outcomes and continue to be a focus of research for new indications and combinations with other treatments.

5.2 Diagnostic Applications

In diagnostics, monoclonal antibodies are used in various assays, including:

- ELISA: For detecting proteins, hormones, and pathogens in clinical samples.

- Immunohistochemistry: For visualizing specific antigens in tissue sections, aiding in cancer diagnosis.

The specificity of monoclonal antibodies enhances the accuracy of diagnostic tests, making them essential tools in clinical laboratories.

5.3 Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of monoclonal antibodies is rapidly evolving, with several emerging technologies and trends, including:

- Bispecific Antibodies: These antibodies can bind to two different antigens, offering new therapeutic strategies.

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Combining monoclonal antibodies with cytotoxic drugs to target and kill cancer cells specifically.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Enhancing antibody discovery and optimization through advanced sequencing technologies.

As research continues, the potential applications of monoclonal antibodies are likely to expand, leading to new therapeutic and diagnostic innovations.

Conclusion

Crafting custom monoclonal antibodies is a complex but rewarding process that involves careful planning, execution, and optimization. From understanding the science behind monoclonal antibodies to designing the antigen, immunizing the animal model, generating hybridomas, and characterizing the antibodies, each step is crucial for success. The applications of monoclonal antibodies in therapeutics and diagnostics are vast, and ongoing research continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in this field.

By following this comprehensive step-by-step guide, researchers and practitioners can navigate the intricacies of monoclonal antibody development, ultimately contributing to advancements in medicine and biotechnology. The future of monoclonal antibodies is bright, with new technologies and applications on the horizon, promising to enhance their impact on human health.